4 June – 5 September 2024

theDock Centre for Social Impact

300-722 Cormorant St, Victoria, BC

M-F 8:30am-5:00pm

Photographic work by: George Magaraia

Documentary Films by: Regina de Paula

Curated by: Desirée Leal

Statement by curator, Desirée Leal:

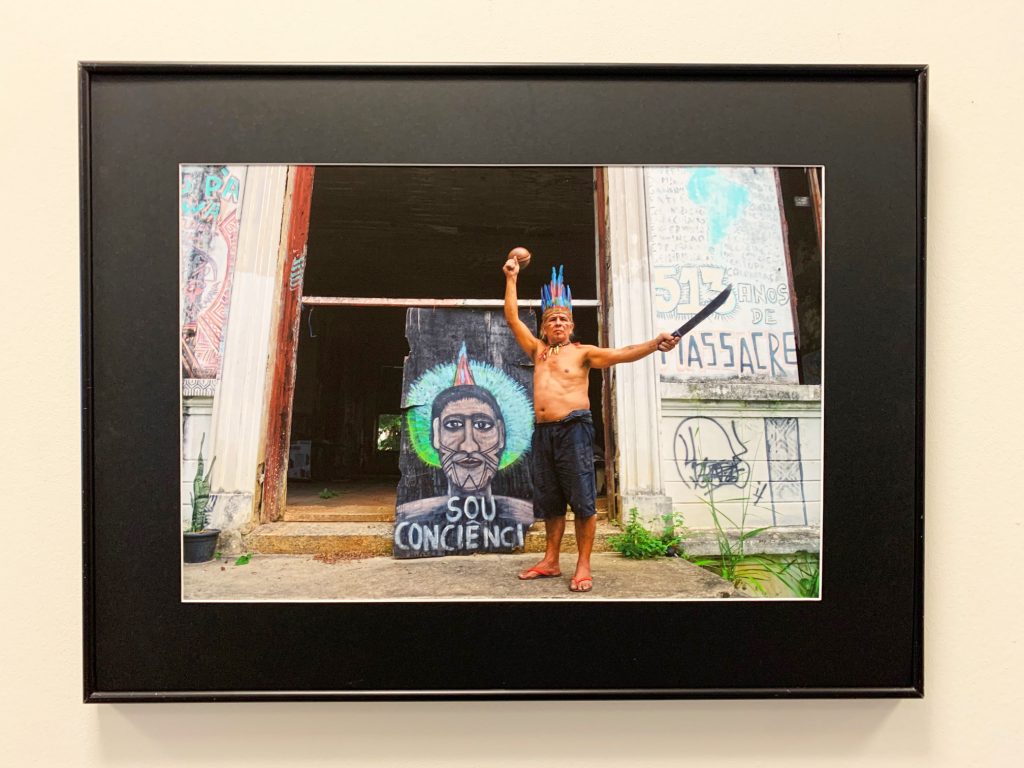

In 2007, the city of Rio de Janeiro won the bid to host the 2014 FIFA World Cup having won the 2016 Olympic bid only seven months before. Immediately governments both local and federal began to busily plan and build in preparation for the events. Among the sites to be improved was the site of the Aldeia Maraka’nã, (Maraka’nã Village). It is the former site of the Indigenous Museum in Rio de Janeiro founded by Anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro in 1953 and has stood abandoned since 1977. The site was occupied by a group of local Indigenous individuals in 2006 and neighbours the Maracanã Stadium, which was built to host the 1950 FIFA World Cup.This site, due to its size and proximity to the stadium, was considered prime real estate for development for the upcoming 2014 World Cup games as additional parking for the stadium and as a site for commerce. The case for development has always been the primary means for justifying colonization and globalization. Expansion into Indigenous lands, displacement and genocide of Indigenous people by European settlers morphed from outright armed warfare into an uneasy dance of reconciliation and recognition that not only still falls short of restoring stolen lands, but also continues to displace, impoverish and devastate Indigenous communities throughout the Americas for the sake of pipelines hydroelectric dams, and in the case of Maracanã, additional parking. Large-scale international events such as the Olympic Games and the World Cup, seek to shine the spotlight on the wealth and cosmopolitan beauty of the world’s major cities to prop up this notion of development and progress that is rooted in colonial values of exploitation and is sustained by the consumerist ideals of industry and globalization.

Holding ceremony and tearing up asphalt for the growing of squash, corn and papaya, the Villagers have not only reclaimed a site that once stood as colonial interpretation of Indigenous culture and history but are re-establishing that site as a living and breathing settlement where traditional ways go beyond the museum display. They do not depict, but rather, live in traditional ways, in the midst of the sprawling urban centre built by European colonizers and maintained by American ones. In this manner the stand taken by the Maraka’nã Villagers not only underscores the heavy price of colonialism, but also perhaps points the way to a new model of development, as traditional ways may be allowed to flourish and evolve beyond industrialization and its demands.

Statement by photographer George Magaraia:

Translated from Portuguese to English by Desirée Leal (below)

A ocupação indígena chamada atualmente de Universidade Indígena Aldeia Marakanã acontece desde outubro de 2006. Minha participação e frequência começa em 2012, quando, já neste ano, pude registrar a festa do Moqueado do povo da etnia Guajajara. Em 2013 os indígenas foram expulsos do território em ação violenta do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, que justificou esta ação como de interesse preparatório para os eventos esportivos da Copa do Mundo de Futebol de 2014 e Olimpíadas do Rio de Janeiro de 2016. Terminado estes eventos os indígenas reocuparam o território, onde estão ininterruptamente desde 2016, resistindo física, jurídica e espiritualmente.

Quando se fala em questão indígena no Brasil, deve-se levar em conta que segundo censo do IBGE de 2010, 48% desta população é menor de 19 anos. Na Universidade Indígena Aldeia Marakanã a comunidade é composta de famílias indígenas e apoiadores, no entanto, não se tem uma presença significativa de jovens e principalmente crianças proporcionalmente em comparação com a média na maioria das aldeias indígenas brasileiras. Poucas crianças habitam aquele espaço. O trabalho aqui proposto tenta de algum modo refletir e ampliar a luz da presença destas poucas crianças.

O trabalho de registro fotográfico, para além de documentar o cotidiano e os eventos ocorridos no local, é um olhar de sensibilidade e de busca por essas crianças, quando elas iluminam a aldeia com essa ancestralidade pulsante nas suas histórias e brincadeiras. A fotografia propõe-se então a apresentar uma perspectiva de resistência, evidenciando uma ancestralidade que se mostra anterior e mais potente que qualquer sistema.

Aproveitando esta breve apresentação, como aluno da Universidade Indígena Aldeia Marakanã, agradeço aos mestres Potyra e Urutau que tanto me inspiram. Este trabalho é de alguma maneira também fruto do trabalho deles em mim. É preciso reconhecer toda articulação, luta, resistência e fonte de conexão com a cultura indígena que esse espaço e toda sua comunidade representam. É um espaço que tem significativo valor de preservação da cultura indígena e de representação dessas populações. Em meio ao contexto urbano da cidade do Rio de Janeiro, ali estão os representantes ativos de diversas populações, que fazem deste local um espaço de retomada de seus espaços, materializando em lutas e pautando pelo reconhecimento aos seus direitos fundamentais.

Com esse trabalho, busca-se a capacidade de desenvolvermos uma perspectiva de sensibilidade sobre as vivências das crianças dessa comunidade, que seja capaz de despertar um ‘reencanto’ com a ancestralidade e possa ‘indigenizar’ os olhares, buscando iluminar as pessoas que vierem a se conectar com esse trabalho, dando maior força a todo esse caminho da resistência.

English Translation:

The Indigenous occupation currently known as Universidade Indígena Aldeia Marakanã has been active since October 2006. My participation and attendance began in 2012, when, that year, I was able to document the Moqueado festival of the Guajajara people. In 2013, the Indigenous occupants were expelled from the territory by violent action by the State of Rio de Janeiro, which justified this action as being in the interest of preparing for the sporting events of the 2014 Football World Cup and the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics. The Indigenous group reoccupied the territory, where they have been engaged in educational and community building actions uninterruptedly since 2016, resisting physically, legally and spiritually.

When talking about Indigenous issues in Brazil, it must be taken into account that according to the 2010 IBGE census (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica/ Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics)*, 48% of this population is under 19 years of age. At the Universidade Indígena Aldeia Marakanã the community is made up of indigenous families and supporters, however, there is not a significant presence of young people and especially children proportional to that of the average in most Brazilian indigenous villages. Few children live in that space. The work exhibited here tries to somehow highlight the presence of these few children.

The work of photographic recording, in addition to documenting daily life and events that took place there, is a look of sensitivity and search for these children, when they illuminate the village with this pulsating ancestry in their stories and games. Photography then proposes to present a perspective of resistance, highlighting an ancestry that appears to be prior and more powerful than any system.

As a student at the Universidade Indígena Aldeia Marakanã, I would like to take this opportunity to thank masters Potyra and Urutau who inspire me so much. This work is in some way also the result of their work on me. It is necessary to recognize all the articulation, struggle, resistance, and source of connection with the indigenous culture that this space and its entire community represent. It is a space that has significant value in preserving indigenous culture and representing these populations. Amid the urban context of the city of Rio de Janeiro, there are active representatives of different populations, who make this place a space for reclaiming their spaces, materializing in struggles, and seeking recognition of their fundamental rights.

With this work, we seek the ability to develop a sensitive perspective on the experiences of children in this community, which is capable of awakening a ‘re-enchantment’ with ancestry and can ‘Indigenize’ the gaze, seeking to enlighten the people who come to connect with this work, giving greater strength to this entire path of resistance.

*The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics is the agency responsible for official collection of statistical, geographic, cartographic, geodetic and environmental information in Brazil.

The Victoria Arts Council is grateful to Aldeia Maraka’nã, artists George Magaraia and Regina de Paula, and curator Desirée Leal, for allowing us to share this amazing story and work at theDock: Centre for Social Impact in Victoria, BC.